I was invited to preach the Easter sermon at the Living Interfaith Church just north of Seattle today. Below, you will find the sermon I wrote. In fact, I didn’t actually preach this sermon. At the last minute, God told me to put my manuscript aside and speak the words the Spirit would give me in the moment. In the message I gave, I used John 4 and Robert Barclay’s words, “I found the evil weakening in me and the good raised up”. That became the core of the message and the query I gave them for the open worship time. Anyway, here is the sermon as written:

Thank you for inviting me to come to your church this morning to talk about Quakers and Easter.

I have to tell you that this is a bit challenging. You see, traditionally, Quakers don’t celebrate special religious days and events according to the calendar. Instead, we throw ourselves into the spiritual event. What is the spiritual significance of Jesus’ death and coming to life again?

You may be wondering why we would neglect the external celebration, when all the other denominations in the Christian family make Christmas and Easter the centerpiece of church life?

Quakers look at passages like John 4 more literally than most. In John 4, Jesus is in Samaria and meets a nameless woman at the well. She understands Jesus to be a prophet, and asks him where people are supposed to worship, on a mountain in Samaria like her people do, or at the temple in Jerusalem. Jesus replies “a time is coming when you will worship the Father neither on this mountain nor in Jerusalem. … a time is coming and has now come when the true worshipers will worship the Father in the Spirit and in truth… God is spirit, and his worshipers must worship in the Spirit and in truth.”

What Quakers have taken this to mean is that when we think of Christmas or Easter, we consider the spiritual meaning of Christmas and Easter.

What do I mean by “spiritual Easter.” What is the spiritual significance, or spiritual event, of Easter, from a Quaker perspective?

Let me read to you a quote from George Fox, one of the founders of Quakerism, from around 1650: “I saw also, that there was an ocean of darkness and death; but an infinite ocean of light and love, which flowed over the ocean of darkness. In that also I saw the infinite love of God.” Death, evil, humiliation, do not have the last word: love does.”

And then there’s another sense in which the early Quakers talked about this Easter phenomenon: “it is the medium whereby we can rise in dominion over our earthly nature, as we feel [the divine] spirit rise in us to do away with sin, and to put an end to transgression; and this is a lesson of daily experience to all those who know by the powerful influence of his spirit working in us, raising the mind above all outward laws… James Bellangee, 1854

So Easter is not just about Jesus dying and coming to life again, but every human being’s soul rising above the constraints of our broken, flawed, human nature.

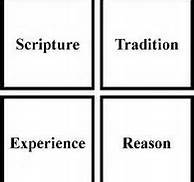

I’ve read these quotes to you from the words and lives of some Quakers from history. That’s good. Nothing wrong with that. We don’t have any creeds or official teachings of any kind from which I could draw to talk about Easter. Because to Quakers, creeds cause arguments, and no words can come close to describing the reality of God anyway. The Bible, when read literally, can be interpreted to mean any number of things. So, far more important than the words of the Bible, or the words of early Quakers, or any creeds, are God’s words straight into each heart.

What is most important is what the divine reveals inwardly to each one of us. Because Quakers believe that God speaks directly into the heart of every one of us. It’s an absolutely fundamental part of Quaker faith. Here are the words of Margaret Fell, another one of our founders, in 1694.

‘Christ saith this, and the apostles say this;’ but what canst thou say? Art thou a child of the Light, and hast thou walked in the Light, and what thou speakest, is it inwardly from God?” This opened me so, that it cut me to the heart; and then I saw clearly we were all wrong. So I sat down in my pew again, and cried bitterly: and I cried in my spirit to the Lord, “We are all thieves; we are all thieves; we have taken the scriptures in words, and know nothing of them in ourselves.”

So what’s important to Quakers is to “know the scriptures in ourselves”. We know what scriptures describe as our own experience.

The most authentic way for me to share a Quaker Easter with you is to invite you into your own encounter with the Divine. A lot of the Quaker experience is just sitting in silence, being still, listening, waiting, molding ourselves to God’s will. Some of us never have mystical experiences. But we do rely on the experiences we have in worship – mystical, an insight, a sense of peace, some words that come to us, an AHA! – as the most authentic source of authority I offer you today is the opportunity to know inwardly, to encounter the meaning of the resurrection in yourself.

I’m going to read the Bible passage to you again, in a slightly different translation, and then I’ll give you a few queries. Queries are open-ended questions for reflection. They don’t have answers, really, but are a way to give the mind/soul/spirit both focus and spaciousness to go wherever the Divine leads:

Luke 24:1-12

Queries:

1. Put yourself in Peter’s place. You’ve just buried your best friend and spiritual teacher, and now his grave is empty. You’re puzzled, shaking your head. What do you imagine Peter is experiencing?

2. Think back to an incident in your life that started with seemingly insurmountable difficulty or pain, but eventually turned out OK or even life-giving in a way you couldn’t have imagined at the outset. How is that experience similar to or different from what you think of as “resurrection”?

3. What does “resurrection” mean to you? How is this different from earlier conceptions of what “resurrection” means? What brought about this shift?